The Fun and Finesse of Translating Comics – An Interview with DIANA SCHUTZ

- Andrew Irvin

- Oct 17, 2022

- 10 min read

Updated: Nov 7, 2025

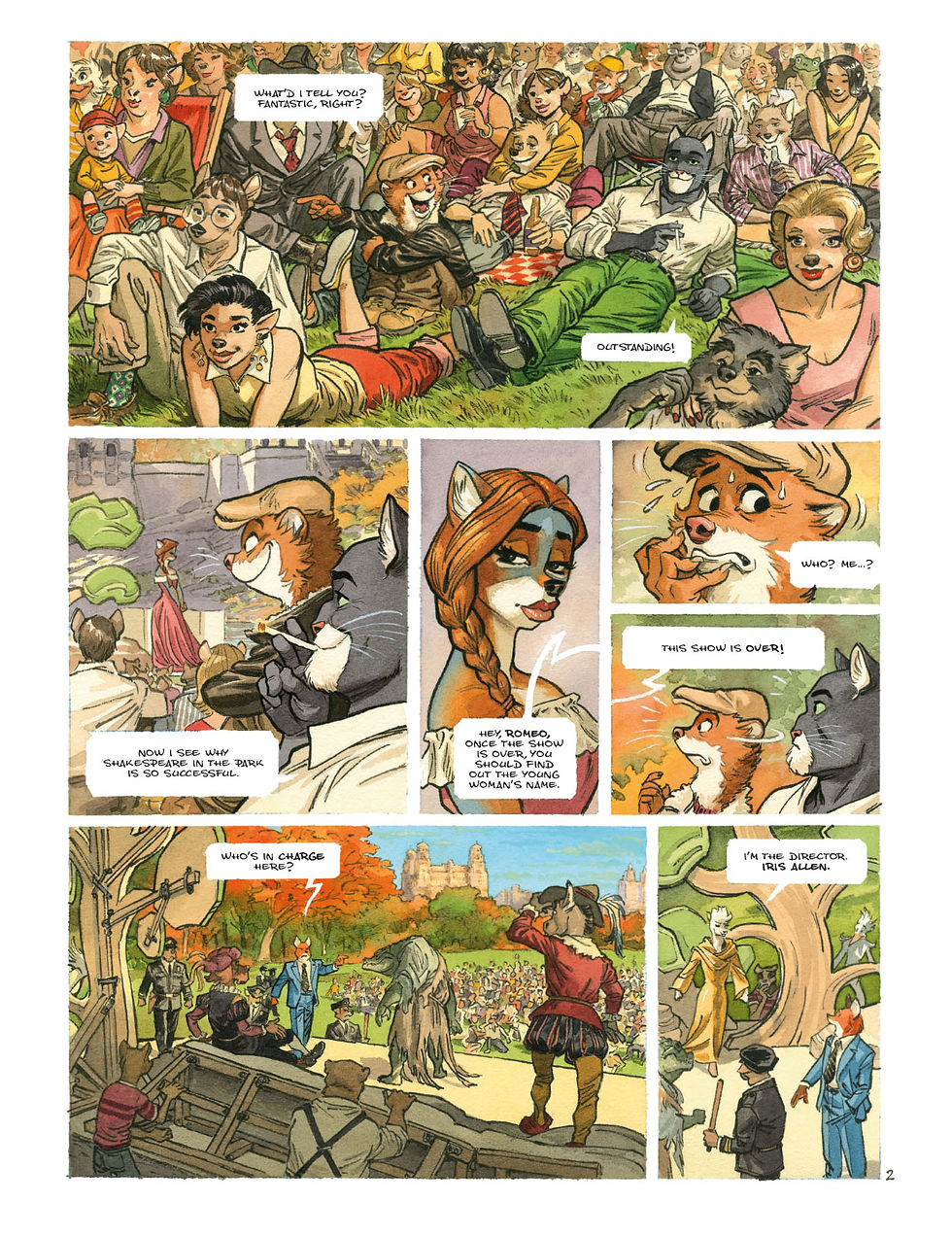

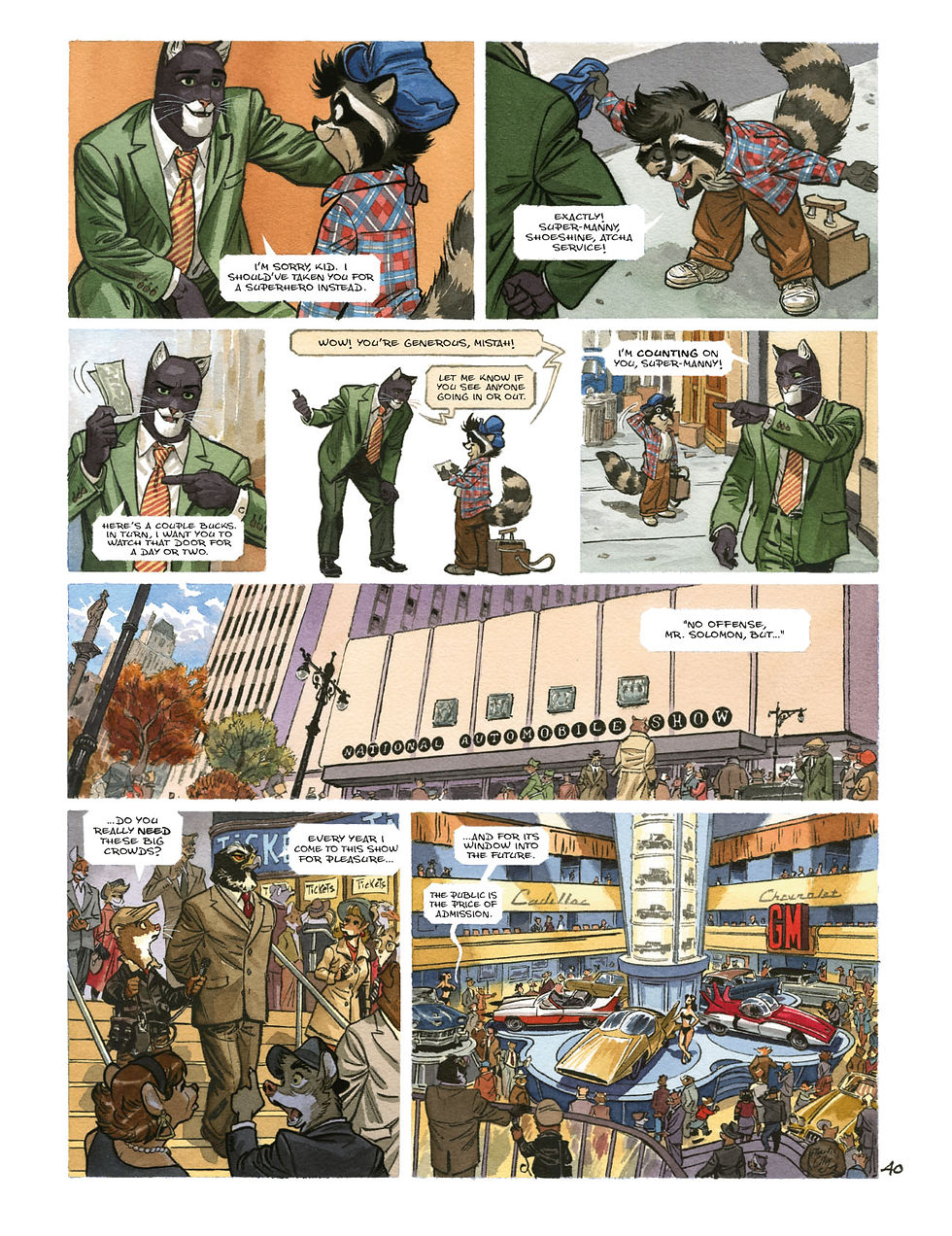

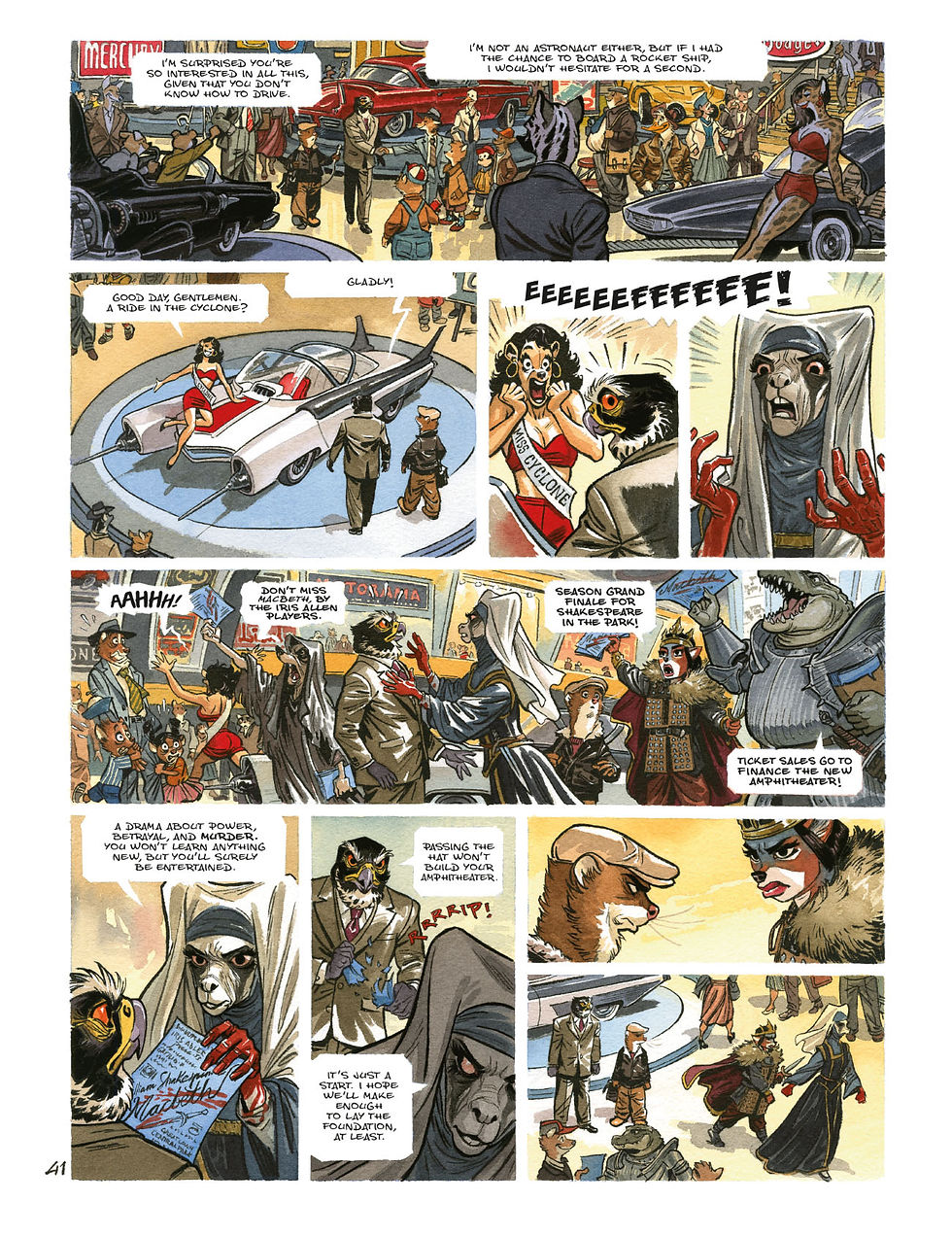

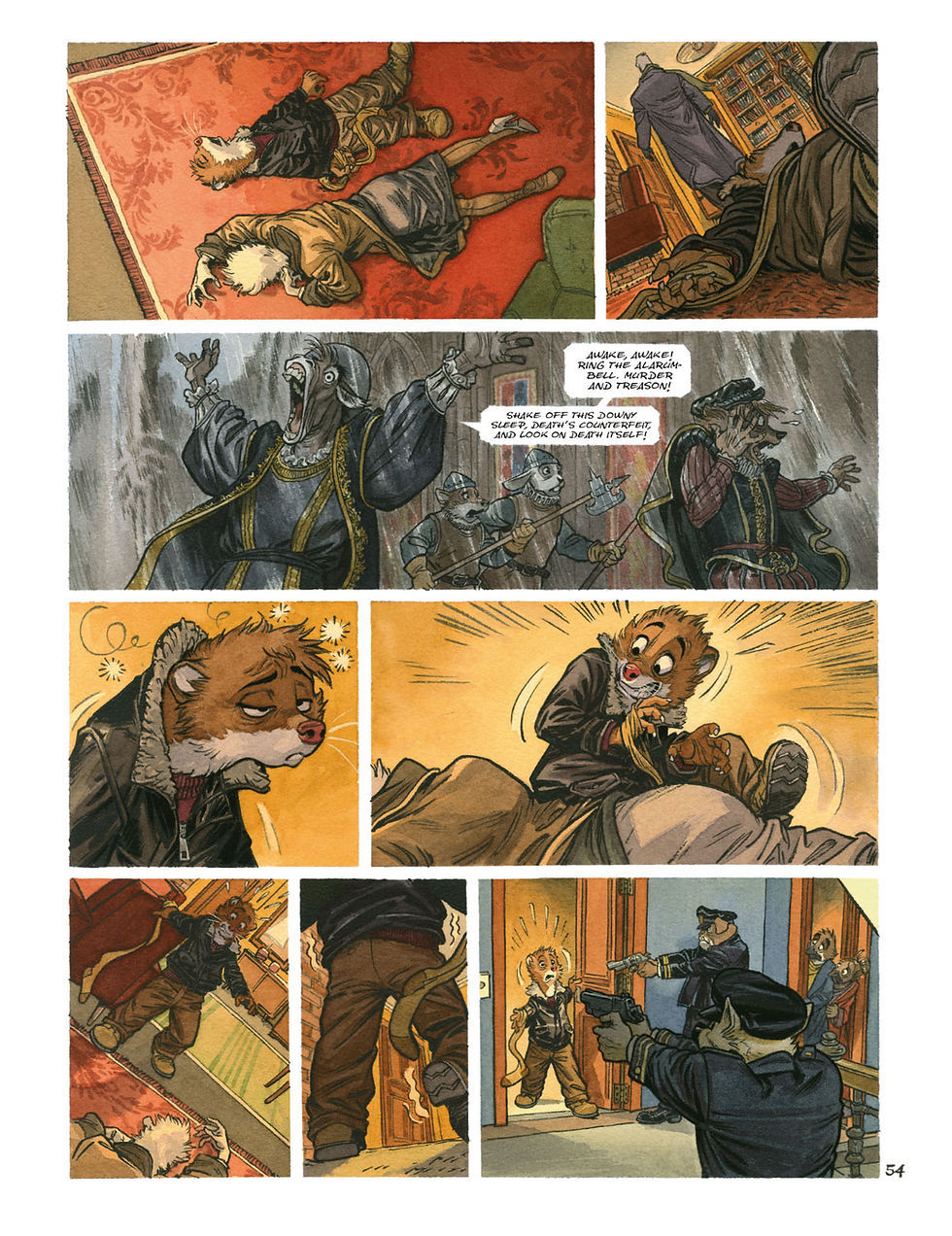

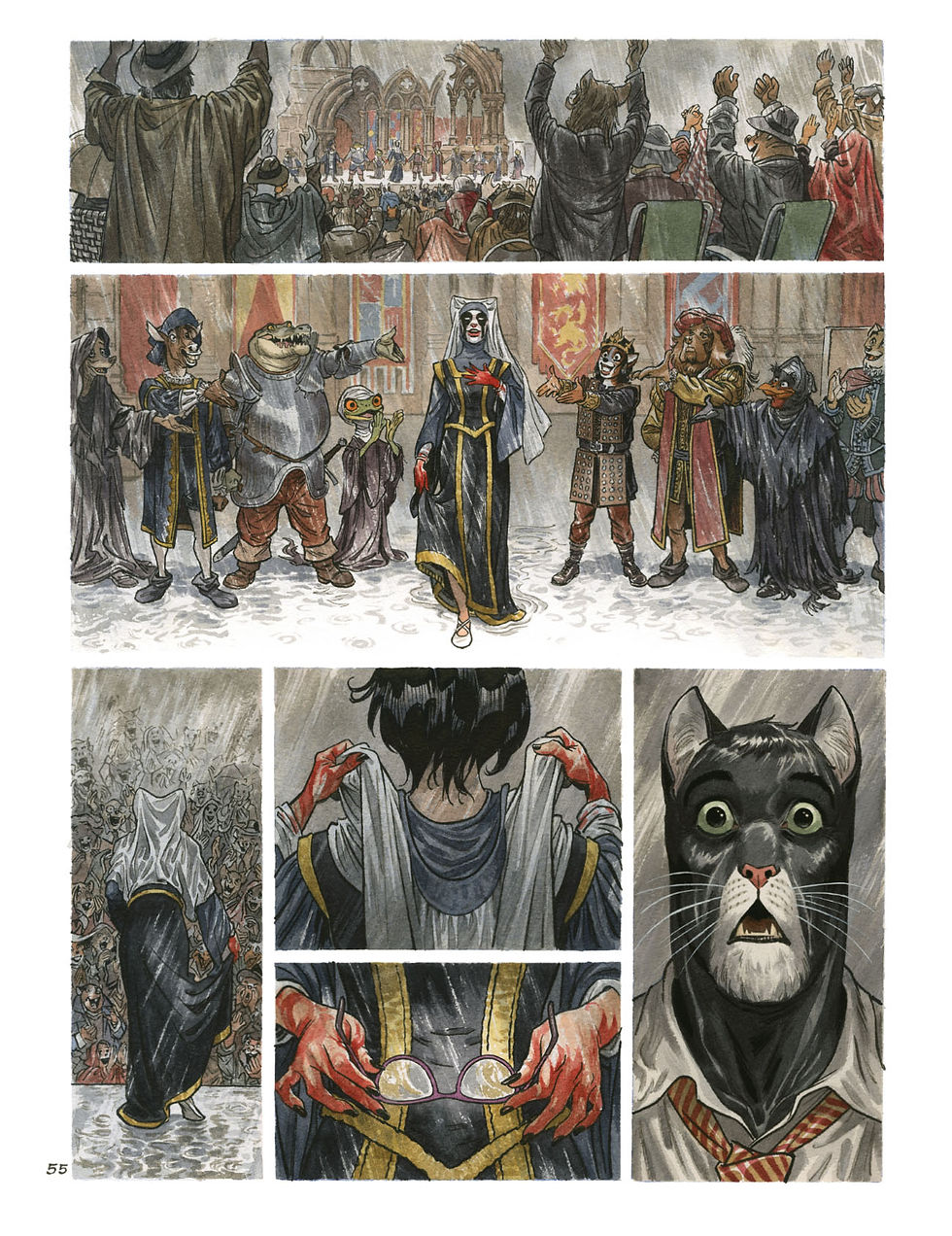

Comic Book Yeti Contributor Andrew Irvin welcomes Diana Schutz into the Yeti Cave to discuss the most recent volume of Blacksad — Blacksad: They All Fall Down: Part One. Diana worked on translating this recent volume and was the editor of the three previous English-language volumes. This is a fantastic chat about a fantastic series!

COMIC BOOK YETI: Thank you for taking time to chat with us today, Diana. I hope all is well in your corner of the world.

DIANA SCHUTZ: Hi! Thanks for having me here.

CBY: Let’s start with your introduction to Blacksad. How did you learn about the title initially, and were you aware of it prior to starting on the first of the three volumes you’ve now translated?

DS: One small note: I’ve edited the last three English-language volumes of Blacksad for Dark Horse, beginning with A Silent Hell, which was published in 2012. However, aside from two very short backup stories in that book, I’ve only translated the most recent volume, Blacksad: They All Fall Down • Part One—a co-translation, in fact, with Brandon Kander. Of course, as a longtime comics editor, I almost always helped finesse final translation scripts for any international books within my editorial purview, including Blacksad.

But to answer your question: yes, absolutely! I’ve loved Blacksad since I first saw Somewhere within the Shadows at my local comics shop, back in 2003. Before the book’s English-language rights came to Dark Horse in 2009, the late Byron Preiss had published the first two story arcs as individual oversized softcover editions, and Byron’s ibooks versions were my introduction to Blacksad. Though I knew nothing about the series at that time, I was immediately drawn to Juanjo Guarnido’s lush watercolor art for that first cover, and as Frank Miller’s then-editor of Sin City, I’d long had an interest in crime fiction. So, when Blacksad was offered to Dark Horse, I was all over it!

CBY: Stepping back further, how did you get involved in translation? How much of your translation work involves graphic novels and comic books? What do you enjoy most about translating work like Blacksad?

DS: You know, I’ve been reading European graphic albums my entire life, starting with the original French editions of Tintin by Georges Remi, aka Hergé. I grew up in Montréal, the child of first-generation Ukrainian and German immigrants, and though we were an anglophone family, Montreal is a largely French-speaking, very cosmopolitan city, and my entire elementary education was in French. I later supplemented my language learning with Latin, German, Spanish, and even a little Italian. Which doesn’t, by the way, mean that I can speak or even read all those languages. Language is like any other skill—use it or lose it—and it’s been a long time since I’ve actively used Latin! Though it has come up, once or twice, in the context of a translation.

While I read a great deal of prose fiction, all my translation work involves comics. I’m a comics fan—and have been, my whole life: I’ve been working in comics since 1978, primarily as an editor, but now that I’m more or less “retired,” translation is something I do because I enjoy it. Blacksad is especially fun to translate because of its Fifties noir element.

CBY: I’m sure our readers will appreciate the inner workings of this absolutely critical aspect of the industry when it comes to enjoying stories from other cultures, so can you tell us a bit about how translating in partnership with Brandon Kander works? How does the division of labor break down for the two of you?

DS: Brandon grew up in Montréal as well—which is where we met, as teenagers—and became an English/ESL educator, teaching there and abroad, though he also took on French-to-English translation work for both the Canadian and Québec governments. But Blacksad presents a singular challenge for its translator(s): Juan Díaz Canales writes the original script for each book in his native Spanish, but the “official” script is always the final, lettered French translation, in part because the book’s primary publisher is Dargaud, which means that their edition is always the first to be released. And right up until deadline, as Juanjo Guarnido is adding the finishing touches to the art, he’s also refining that French translation script in order to integrate it as well as possible with his drawing. In a perfect world, then, Blacksad’s translators should have both French and Spanish at their command.

With They All Fall Down, Brandon took the first pass, translating into English from Dargaud’s official, lettered French script, and I wrote the final English-language script, revisiting Brandon’s work in light of Juan’s original Spanish script as well as Dargaud’s French translation (by Christilla Vasserot). This is a case where having studied both French and Spanish is a huge benefit. I should also mention that Brandon is an exceptional grammarian, so he is the handy adjudicator of any English grammar concerns.

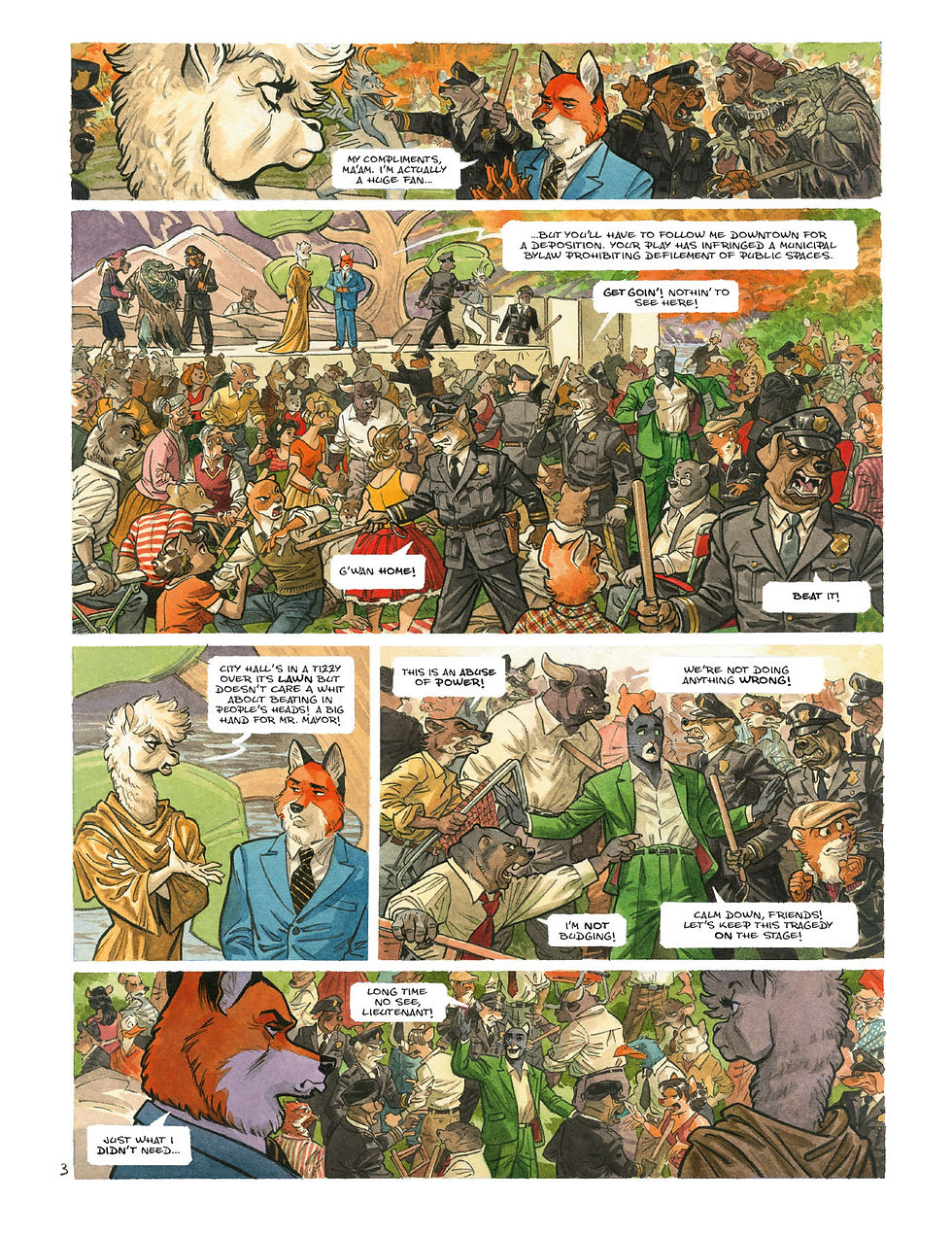

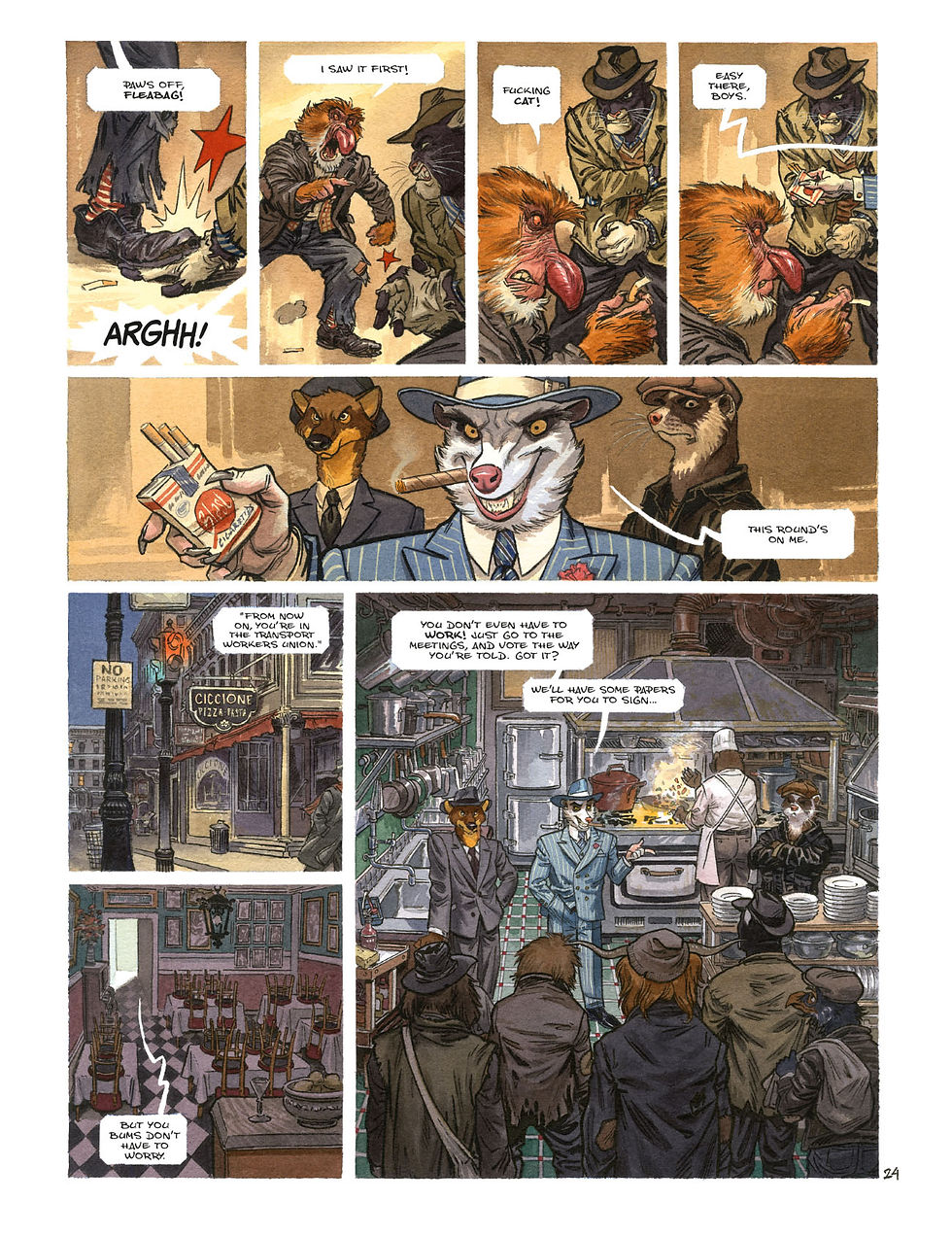

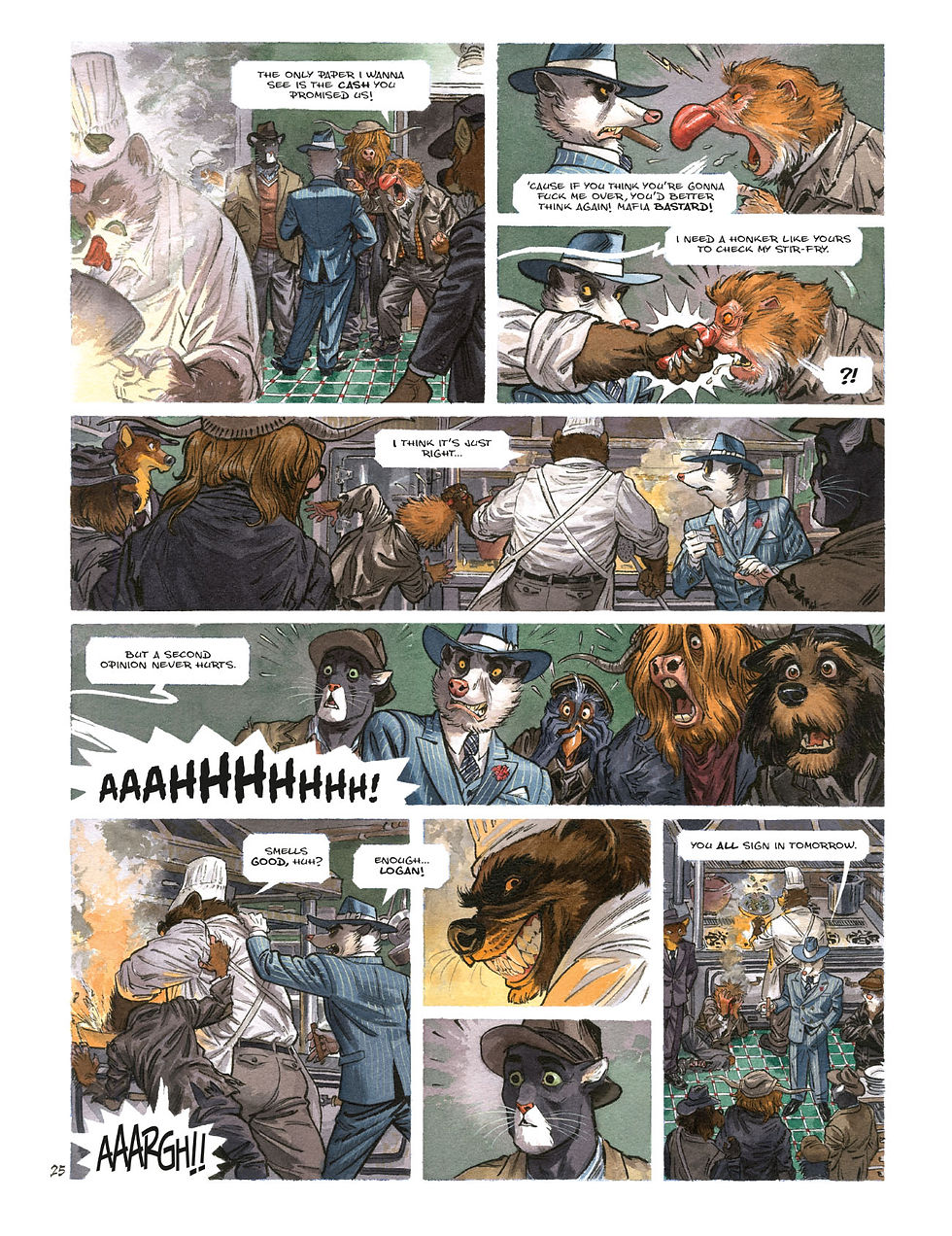

CBY: The interspecies interaction is a proxy for racial and class issues amongst the various ethnic groups historically tied to various occupations and sectors in New York. Seeing as Juan Díaz Canales and Juanjo Guarnido aren’t native New Yorkers, how much of this is infused through their research and experience, and how much is augmented by your touch in the localization process?

DS: Well, the creators’ research for the series is absolutely impeccable. Juan and Juanjo are clearly in love with mid-century Americana, and they’ve done their homework, so there’s no need for me to impose my own sensibilities on their creation. And I think you’ll find that many, if not most, professional translators consider “localization” as an integral part of our overall process; we don’t really make a distinction there. That said, Juan and Juanjo do give me a certain leeway. For example, there’s a scene early in the new book where some New York street toughs attempt to mug union leader Kenneth Clarke, and I wrote their dialogue in slang. I mean, New York street slang simply doesn’t exist in Spanish or French, but it made sense to write it in, into the English script. Shakespearean English also doesn’t exist in Spanish or French, and when you read the book in either of those two languages, you can’t tell that it opens in the midst of The Tempest—which makes that first scene quite a bit more ominous than it is in English, but we opted for the traditional Shakespearean text, which is what the creators preferred. And that’s our guiding principle: creator preference.

Which is not to say that we don’t catch mistakes. You live and breathe a book for the length of time you’re translating it—which, in my case, is longer than most, because I’m an impossibly slow writer, and I don’t do this to make a living; I do it largely for pleasure. But in the process of translating They All Fall Down, I caught a couple mistakes, and then again, in the process of editing the English-language edition for Dark Horse, I caught another, more serious error, but in all cases, we brought these to the creators’ attention and fixed them for the Dark Horse book. We’re actually really lucky that Juan and Juanjo are so invested in the American edition of their work. It makes my job a lot easier, knowing I can reach out to them at any time.

CBY: In Solomon, it seems we have an analogue to Robert Moses (who, as a sustainable transport professional, I consider one of America’s grand villains). How do you capture the tone and trappings of a very consequential aspect of New York City history in this alternative, anthropomorphized dressing of the urban environment?

DS: Solomon is a complex character. You’re quite right: he’s based on the real-life Robert Moses, an urban planner of apparently questionable ethics. I can’t speak for Moses, who, in part, was a man of his time—when “sustainability” wasn’t the watchword it is today. Wasn’t even on the horizon. Solomon, on the other hand, is intended to be an asshole! But a visionary, too—which makes him more interesting, as a character. Problem is, his particular vision is at the expense of public transport—and therefore at the expense of lower-income populations. And his means of achieving his ends are ruthless. John Blacksad, on the other hand, is a man—well, a cat—out of time. He’s the conscience of the book. His attitudes are more enlightened, more contemporary than those of his fellow characters, even Weekly. They All Fall Down isn’t meant to be historical nonfiction, though we all do our best—creators and translators—to remain true to the period. I try to stay away from language that’s too modern, for instance. But the stories can be interpreted as morality plays, with Blacksad ironically providing the human element, the heart of the tale.

CBY: I appreciated the translation notes included at the end of They All Fall Down, and how they addressed the ample references to Shakespeare and other cultural touchstones from reality, such as mention of “That Old Black Magic,” or brands like General Motors and Chevrolet. How is it decided between you and the creators what to keep intact from our world, and what requires adaptation or parody?

DS: Oh, so glad you appreciated the translation notes! Honestly, I could have used two or more pages for those. But I’m not sure I can answer your question, really. I think that one is probably for the creators. It’s their story. The English-language scripting is ours, Brandon’s and mine, but all the story elements are theirs, and that would include decisions regarding what to keep intact—or not—from the real world.

CBY: The script is peppered with aphorisms—“Cat got your tongue,” “eating crow,” “dogfight on your hands”—and idioms don’t necessarily translate across cultures cleanly. Do you find more similarities with the idiomatic dialogue between the Spanish or the French translations? What goes into ensuring the turns of phrase remain within the text without compromising the intent of the dialogue in moving forward the plot or emphasizing the traits of specific characters (i.e., how much license to deviate are you provided)?

DS: Thanks for noticing the animal metaphors! I worked pretty hard to incorporate as many as I could into our final script. And you’re right: they don’t translate over, so most of them weren’t in either of the source scripts—but the English metaphors do faithfully translate the original meanings in those cases.

Spanish and French—and Italian and Portuguese—are basically all the same language! If you know one Romance language thoroughly, it’s pretty easy to learn the others. Grammatical structure and vocabulary terms are very similar. So, yes, Spanish and French share many more idioms than, say, Spanish and English. But “turns of phrase,” like idioms, depend on verbal cues, whereas translation, particularly when it comes to fiction, is about capturing meaning, clusters of meanings, and expressing them as well as possible in the target language—which, in our case, is English—and using everything English has to offer in terms of its own intrinsic literary qualities. As long as meaning is preserved, original intent is maintained.

I wouldn’t deviate unless there were a very good reason to do so—and the creators would have to approve. Blacksad is a creator-owned book, and I’ve spent my entire career working to respect creators’ rights and interests at all times. But, for example, the original title—in both Spanish and French—translates literally as Everything Falls. And though that phrase is quite a bit sharper in Spanish, Todo Cae, it sounds a bit lifeless in English, unfortunately, so I proposed They All Fall Down instead, which, I think, sounds more like the title of an American detective novel from the Fifties. Turns out, Juan’s original title is taken from some dialogue that he wrote for Part Two of the story, where, luckily, “they all fall down” works even better in English than “everything falls,” so both creators were very cool with that change—which, as the book’s title, is a pretty significant one.

CBY: I’m curious if as a translator, you’ve cultivated a habit of avid reading. Can you give us a bit of a background on your favorite literary work, and influences on your approach to linguistics and integration of multilingualism into your review and digestion of texts? Any recommendations around key texts or methods for picking up the nuances required for apt translation in case any of our readers are interested in broadening their literary horizons beyond work written in English?

DS: I’ve been a voracious reader of fiction since I first learned how to read. But aside from French and Spanish graphic novels, I don’t read nearly enough in other languages, if that’s your question. To be honest, I’m kind of a literary snoot: I read as much for how something is written as for what is written. Which is to say I’m fond of writers who possess a flair for language —something that isn’t all that popular in contemporary fiction. But, for instance, writers like Michael Chabon and Glen David Gold—both of whom I had the great pleasure of working with, as editor of some of their first comics scripts—really understand how to manipulate English in complex ways that afford the reader tremendous pleasure, not only in the story per se, but in the structure of their sentences, in their specific choices of metaphorical language, in their unusual and precise word usage. Amor Towles and Pulitzer winner Richard Powers are two more modern examples. Female stylists would include writers like Ruth Ozeki, Rachel Cusk, and my longtime inspiration, Margaret Atwood.

These are all English-language writers who, of course, speak to my own experiences, but fiction allows us to broaden our scope to other cultures as well, to live inside people and places that are wholly unfamiliar—to inhabit perspectives that are widely different from our own. With that in mind, I strongly recommend reading internationally, and in that case, translation is crucial. A current favorite is Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk, whose novel Flights won the 2018 Man Booker International Prize, an award that is shared with the translator: in this case, Jennifer Croft, who did a remarkable job. Jamie Chang, who translated Korean author Cho Nam-ju’s novel Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982, describes the process of literary translation as “like taking a watercolor-on-paper landscape painting and copying it in oil on canvas—same landscape, different everything else.” I love that. Because preservation of meaning is just the start of the translator’s job—the work also has to sing in English! I’m talking about things like rhythm and flow, cadence and voice—all of which are language-dependent and, thus, have to be written into the target English.

The Booker International Prize is a great place to seek out translated literature, but, really, we publish so little work-in-translation here in the U.S. that almost anything that’s been translated into English is bound to be a cut above.

CBY: So apart from your earlier influences that have driven your work as a translator, what do you see out there in the market that excites you enough to give it a shout-out for our readers? Comics, books, movies, music, etc.—what’s catching your attention these days?

DS: I’ll stick to comics: I’ve just started reading Love Everlasting by Tom King and Elsa Charretier, colored by my good friend Matthew Hollingsworth—and as a fan of pre-Code Joe Simon and Jack Kirby romance comics, I’m impressed by these creators’ new spin on the genre. Of course, as of 2022, we’ve now had forty years of the Hernandez Brothers’ Love & Rockets, the quintessence of contemporary romance and human drama in comics.

CBY: Diana, thank you for sharing your insights and spending your time with Comic Book Yeti.

DS: Thanks very much for your interest! And your thoughtful questions!

Like what you've just read? Help us keep the Yeti Cave warm! Comic Book Yeti has a Patreon page for anyone who wants to contribute: https://www.patreon.com/comicbookyeti